The Epistemic Construction of Space and Its Relationship with Being

From a philosophical perspective, many authors have treated “space” as the place where human activity transcends. In the interstices of ancient philosophy, Parmenides and Democritus discussed the existence of non-being and the void. Plato, for his part, was the first to differentiate between “space” (Chóra) and “receptacle” (Hypodoché), distinguishing what is not in itself but is filled. This latter term would later be linked to the word “placement” and, eventually, to the concept of a geographical region (Barañano Letamendia, 1983). In the Middle Ages, the scholastic Thomas Aquinas analyzed the concepts of “place,” “void,” and “time.” According to Mendoza (1970), this characterization, which is not an essential definition, serves Aquinas in grounding the relevance of the study of place, making him the first author to methodically address an issue of importance for modern philosophy.

In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” Immanuel Kant offers a gnoseological dialogue between the concepts of space, time, and reason. In Kantian philosophy, space is the realm where human perception occurs. Thus, more than a physical location, it is a form of a priori intuition, a structure the mind uses to organize and understand sensory experiences. For Kant, space belongs to the order of phenomena, to the world as it is perceived, inexorably conditioned by time. In summary, for Kant, space is pure intuition and categories of understanding reality as it is.

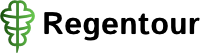

Significantly, it was a neo-Kantian, Jakob Johann von Uexküll (1864-1944), who first proposed the term “Umwelt” (environment, from the German). Through the study of organisms, Uexküll theorized that they could have different environments despite sharing the same surroundings. The concept of “Umwelt” had a radical influence on 20th-century German philosophy and became the central axis around which space studies in the philosophy of subsequent decades revolved (Pérez, 2018), particularly in the phenomenology of Husserl and the epistemological vision of Heidegger.

Illustration 1 – Early Circular Feedback Scheme

Source: Theoretische Biologie (1920)

Husserl emphasizes the role of the body (Leib) in the constitution of space. Delving into this, the author introduces the concept of “spatial horizons,” referring to the expectations and possibilities that unfold in the interconnection and coherence of sensory experience. Additionally, the phenomenological reduction of Husserl’s school provides a distinction between abstract geometric space and the lived space of the surrounding world (Umwelt). The perception of space implies a temporal dimension, as objects are perceived in a continuous flow of experiences. The construction of space in consciousness is, therefore, intertwined with the constitution of time. Husserl’s work concerning space can be traced to later years and has continued through Merleau-Ponty (1957) and, in the cultural and literary realm, through Bachelard (1965).

Perhaps the most recognized philosopher in 20th-century literature who dealt with the theme of space and being was Heidegger. The author introduces the concept of “Being-in-the-world” to describe how human beings exist and relate. He asserts that space is not simply an empty “receptacle” where life happens but is inseparable from the way individuals interact. Heidegger (1927), in his book Being and Time, finds a condition of possibility for being in a surrounding world (Umwelt). Consequently, from his perspective, within space, there are an indeterminate number of relationships that throw humans into their environment, revealed through an activity called “unconcealment.” Although the influence of Jakob von Uexküll on Heideggerian theory is clear, according to Pérez (2018), Heidegger made a significant error: separating man from the animal world, cutting off his intrinsic connection with his nature.

The dimorphism between geometric—or geographic—space and space as a construction of life remains present in countless contemporary philosophers. Bergson (1942), in his book Creative Evolution, separates homogeneous space, that of science, from lived space, which is associated with duration (durée). Similarly, Deleuze and Guattari (2004) introduce the concepts of smooth space and striated space, the former associated with creativity, while the latter is linked to sedentarization and authority. Casey (2004), for his part, differentiates the concept of place from that of abstract space, where memory and identity have a special bond. In conclusion, the Platonic duality is palpable up to the present century and is considered insufficient to address the systemic problems of development models. In this sense, there is a debt from dominant philosophy to Jakob Johann von Uexküll. His concept of environment has been undermined from its foundations.

Studies on Tourist Space and the “Performance Metaphor”

The literature on tourist space is so vast that covering it all is impossible for reasons that are barely obvious (the main one being the brevity of this editorial format). Nevertheless, it is pertinent to introduce a perhaps belated debate to generate an epistemological reflection on tourism planning. With this initial clarification, the literature most relevant to the education of tourism scholars internationally will be briefly discussed, followed by an analysis of some obstacles and difficulties of various kinds.

As an entry point, it is important to clarify that modern tourism is a bourgeois phenomenon born of capitalist accumulation. Although its history is linked to human displacement, pilgrimages, and, to a large extent, road hospitality, tourism as we know it today finds its genesis in the creation of the first recorded travel agency, namely, Thomas Cook’s venture. In this sense, it is only logical that most authors who refer to tourist phenomena and are world authorities on the subject write in English (generally the lingua franca of scientific knowledge).

One of the first theories to address tourist space was the “Central Place Theory.” The geographer Walter Christaller first published his work Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland in German in 1933, a theory that found its greatest recognition in tourism literature in 1966, the year it was translated into English. This work is one of the primary branches of quantitative geography and perhaps the first to use general systems theory to explain the distribution and hierarchy of urban spaces. The model is considered relevant in the literature as it involves elements such as displacement, transportation networks, and the cost of products and services.

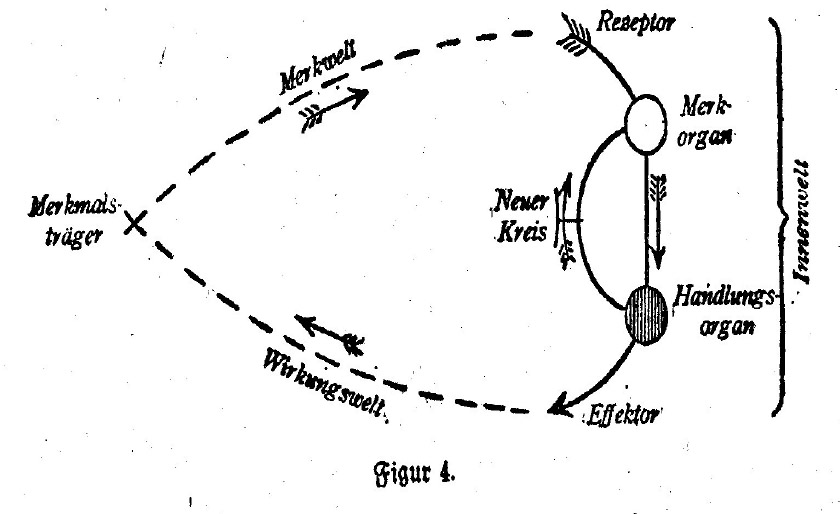

Illustration 2 – Evolution Cycle of a Tourist Area

Source: Butler (1980)

Continuing the proposed analysis, perhaps the most important theory applied to tourist destinations today is Richard Butler’s (1980) model of the destination life cycle. The model analyzes the different evolutionary phases of a tourist destination, dividing its analysis into six stages: exploration, involvement of local authorities, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline or rejuvenation. Butler has proposed pertinent actions for each stage of the growth of tourist destinations in his model. Butler’s theoretical model is widely valued in the academic community, with numerous case studies; one of the most notable is the one addressed by Garay and Cánoves (2011) in Catalonia, Spain.

The 1990s and, in general, the early 21st century have witnessed an explosion in scientific production on “place.” Numerous studies address local identity (Oakes, 1993; Kneafsey, 1998; Hubbard et al., 2000; McIntyre et al., 2006; Ferreira, 2007). Critical studies on place and tourism (Butler & Pearce, 1995; Coleman & Crang, 2002; Ryan, 2007; Castrogiovanni, 2007; Hall, 2013), in addition to research conducted on public policy (Dredge & Jenkins, 2003; Hall, 2003). Regarding tourist space, notable publications address the commodification of space and mass tourism (Edensor, 2001; Clavé, 2012), studies on tourist space and landscape (Shaw & Williams, 2004), and sustainable development in tourist space (Boullón, 2006).

In the Latin American context, a key author in tourism faculties is, without a doubt, Roberto C. Boullón. In his book Planificación del espacio turístico (1985), Boullón describes the concept of tourist space, introduces tourist zoning, defines terms through an extensive glossary, addresses a planning methodology involving resource inventory, and, importantly, formulates strategies for destination sustainability. In this sense, the author is a pioneer, particularly in formulating development plans, monitoring, and evaluation. His theory is supported by numerous practical cases and examples of application in various destinations.

Opening a critical perspective, tourism space planning frequently encounters significant challenges in its territorial application, necessitating a critical examination of the instrumental role tourism plays in shaping space, communities, and cultural identity. According to Edensor (2001), tourism creates a narrative, which he describes as the “performance metaphor.” Tourism is often planned with a focus on competitiveness, with a predominantly productivist language prevailing in its discourse. This emphasis on sustainability, while affirming growth, ultimately prioritizes the attraction of more tourists, leading to the degradation of destinations. In other words, the performance of the economic axis of sustainability is the pillar that supports tourism planning. The outcomes of current planning models are all too evident: gentrification, loss of cultural diversity, pressure on life systems, and the displacement of local communities, among other issues. In this context, research on sustainable tourism must evolve to address these phenomena in a more scientific and critical manner (Zhehua, 2010). For now, despite good intentions, most sustainable tourism planning models fail to adequately respond to these challenges and do not consider the future effects of tourism on local culture.

Illustration 3 – Anthropic Landscape. Salento – Quindío – Colombia

Source: Regentour

Sense of Place in Regenerative Tourism Planning

Topophilia (from the Greek “topos,” meaning “place,” and “philia,” meaning “love of”) is a concept introduced by the British poet John Betjeman in 1948 to denote “love of place.” Tuan Yi-Fu (1974) was the first to explore this term from the perspective of environmental sciences. In his book Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values, Tuan defines topophilia as the emotional attachment people develop towards specific places, derived from their experiences and perceptions. For Tuan, this emotional attachment can manifest as a deep connection, rooted in traditions and beliefs, which are shaped by cultural meanings. Thus, the sense of place fosters the formation of both individual and collective identity.

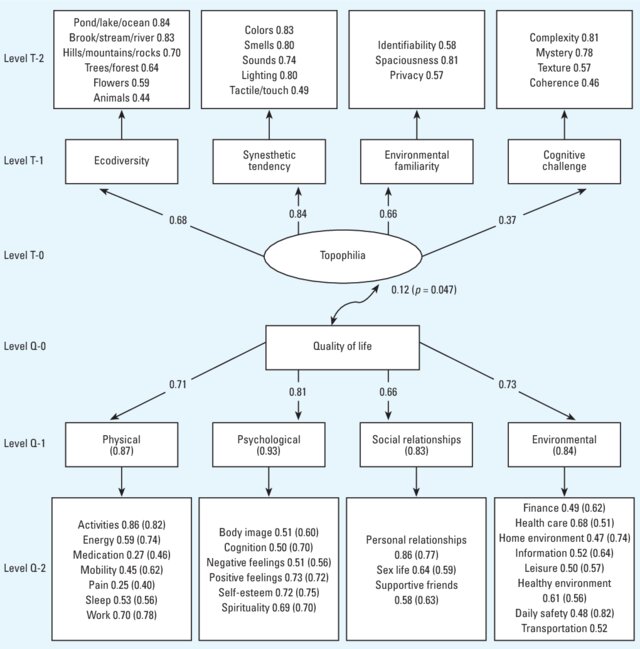

As described in the philosophical introduction of this text, space is composed of a complex network of perceptions, with the physical realm being imbued with cultural meanings. Tuan’s work delves into these relationships, indicating that a profound understanding of attachment to places can facilitate the creation of environments that foster lasting emotional connections. From an academic perspective, Tuan’s sense of place approach is interdisciplinary, blending insights from human geography, environmental psychology, and planning to explore how individuals experience and value their contexts. Topophilia is not an ideologically charged concept; it has quantitative approaches, such as the one proposed by Ogunseitan (2005), who developed a statistical model that associates topophilia with quality of life and its determinants, using structural equation modeling for analysis.

Illustration 4 – The statistical model of the association between topophilia, quality of life and its immediate determinants.

Source: Ogunseitan (2005)

The sense of place contributes a new ethical perspective to the design of activities, including tourism. Vivid space introduces a new iridescence to the illusions proposed by sustainable tourism. The vivid goes far beyond materiality (as inferred from Heidegger), encompassing representations, emotions, feelings, motivations, dreams, and desires. Foucault would refer to this as “heterotopia”—the non-places where the lives of the “others,” the forgotten and marginalized by tourism development, unfold. Tourism should serve not only as a tool for planning but also as a means to give voice to those excluded from traditional development models.

In tourism, the theory of Sense of Place has been applied even before finding its theoretical foundation in regenerative tourism. Although modest, three publications stand out from the 1980s and 1990s: specifically, two studies on authenticity and local identity (Lew, 1989; Hughes, 1995) and another on critical geography theory applied to tourism (Britton, 1991). The new millennium has brought a much broader theoretical development. Three major theoretical bodies can be distinguished: studies that analyze the relationship between sense of place, culture, and tourism (Stokowski, 2002; Derret, 2003; Gu & Ryan, 2008; Smith, 2015; Jepson & Sharpley, 2018; Tan et al., 2018), studies on tourism development (Farnum, 2005; Kerstetter & Bricker, 2009; Amsden & Stedman, 2010; Liu & Cheng, 2016), and those concerning experiential marketing, territorial marketing, and tourism promotion (Walsh, 2001; Haven-Tang & Jones, 2005; Campelo et al., 2014). The listed publications are merely the most relevant; the literature in this field is extensive and continues to grow.

In the context of regenerative development, place-based design has evolved theoretically with the Regenesis Group (a North American consultancy group specializing in regenerative design). The most important text published to date is titled Designing from Place: A Regenerative Framework and Methodology. In this document, Mang & Reed (2012, p. 9) introduce the term “Story of Place” for the first time. In their words:

“[…] History has shown that a society will not sustain the necessary will to implement and maintain required changes, day after day, without invoking the spirit of care that arises from a deep connection to place. Secondly, discovering the story of a place allows us to understand how living systems function and provides greater intelligence on how humans can align with that way of working for the benefit of all. Finally, the story of place provides a framework for a continuous learning process that enables humans to co-evolve with their environment.”

Illustration 5 – Regenerative tourism model – Rancho Margot – Costa Rica

Source: Regentour

Applied to tourism, the story of place plays a significant role. According to the Chilean website Estrategia Global de Turismo Regenerativo (2024):

“To work from a living place and the ‘Sense of Place,’ our capacities are directed toward observing and weaving together the geological, hydrological, and biological history (flora and fauna), ecological dynamics, as well as sensing and observing the patterns that give life to the place and have given rise to the human cultural patterns that develop within it. Just as vegetation has shaped the very environment in which it emerges, transforming it and creating new possibilities of expression and niches for new forms to inhabit, humans too are both created by and creators of their environment.”

In this sense, it is important to clarify that there is no single way to connect locals with the tourist space, to establish intimate bonds between communities and place. The methodologies are diverse, but the desired outcome is the same: a perception linked to love and care for the tourist destination. Referring back to Jakob Johann von Uexküll, it is essential to recognize the notion of “Umwelt,” the perceptible world in which an organism exists as a subject. A new regenerative culture should aim not only to preserve the functional circle of life but to contribute to the health and co-evolution of other living systems and the links that ensure the perpetuity of the planet. This is the new task of regenerative tourism and the work of tourism scientists.

Jhon Enrique Bermúdez Tobón

Ph.D. (c) in Tourism (UAB)

Master’s in Sustainable Tourism Management (UCI)

Sustainable Tourism Administrator (UTP)

Bibliographic sources:

Amsden, B. L., Stedman, R. C., & Kruger, L. E. (2010). The creation and maintenance of sense of place in a tourism-dependent community. Leisure Sciences, 33 (1), 32-51.

Bergson, H. (1942). La evolución creadora.

Bachelard, G., & Champourcin, E. (1965). La poética del espacio (Vol. 183). México: Fondo de cultura económica.

Boullón, R. C. (1990). Planificación del espacio turístico

Boullón, R. C. (2006). Espacio turístico y desarrollo sustentable. Aportes y transferencias, 10 (2), 17-24.

Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24 (1), 5-12.

Butler, R. W., & Pearce, D. (Eds.). (1995). Change in tourism: people, places, processes (pp. xi+-252).

Britton, S. (1991). Tourism, capital, and place: Towards a critical geography of tourism. Environment and planning D: society and space, 9 (4), 451-478.

Campelo, A., Aitken, R., Thyne, M., & Gnoth, J. (2014). Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. Journal of travel research, 53 (2), 154-166.

Casey, E. (2013). The fate of place: A philosophical history. Univ of California Press.

de Barañano Letamendia, K. (1983). El concepto de espacio en la filosofía y la plástica del siglo XX. Kobie. Bellas artes, (1), 137-224.

Castrogiovanni, A. C. (2007). Lugar, no-lugar y entre-lugar: Los ángulos del espacio turístico. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo, 16 (1), 5-25.

Christaller, W. (1933). Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Christaller, W. (1966). Central Places in Southern Germany. Prentice Hall (traducción al inglés de la obra original de 1933).

Clavé, S. A. (2012). Rethinking mass tourism, space and place. In The Routledge handbook of tourism geographies (pp. 230-237). Routledge.

Coleman, S., & Crang, M. (Eds.). (2002). Tourism: Between place and performance. Berghahn books.

Deleuze, G., Guattari, P. F., & Pérez, J. V. (2004). Mil mesetas(p. 159). Barcelona: Pre-textos.

Derrett, R. (2003). Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event Management, 8 (1), 49-58.

Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2003). Destination place identity and regional tourism policy. Tourism Geographies, 5 (4), 383-407.

Edensor, T. (2001). Performing tourism, staging tourism: (Re) producing tourist space and practice. Tourist studies, 1 (1), 59-81.

Estrategia global de turismo regenerativo (2024). Recuperado de: “https://turismoregenerativo.org/2019/09/diseno-de-experiencias-regenerativas/”

Farnum, J. (2005). Sense of place in natural resource recreation and tourism: An evaluation and assessment of research findings.

Ferreira, S. (2007, September). Role of tourism and place identity in the development of small towns in the Western Cape, South Africa. In Urban Forum (Vol. 18, pp. 191-209). Springer Netherlands.

Garay, L., & Cànoves, G. (2011). Life cycles, stages and tourism history: The Catalonia (Spain) experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (2), 651-671.

Gu, H., & Ryan, C. (2008). Place attachment, identity and community impacts of tourism—the case of a Beijing hutong. Tourism management, 29 (4), 637-647.

Hall, C. M. (2003). Politics and place: an analysis of power in tourism communities. In Tourism in destination communities (pp. 99-113). Wallingford UK: CABI Publishi

Hall, C. M., Harrison, D., Weaver, D., & Wall, G. (2013). Vanishing peripheries: Does tourism consume places?. Tourism Recreation Research, 38 (1), 71-9

Haven-Tang, C., & Jones, E. (2005). Using local food and drink to differentiate tourism destinations through a sense of place: A story from Wales-dining at Monmouthshire’s great table. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 4 (4), 69-86.

Hubbard, P., & Lilley, K. (2000). Selling the past: Heritage-tourism and place identity in Stratford-upon-Avon. Geography, 221-232.

Hughes, G. (1995). Authenticity in tourism. Annals of tourism Research, 22 (4), 781-803.

Jepson, D., & Sharpley, R. (2018). More than sense of place? Exploring the emotional dimension of rural tourism experiences. In Rural tourism (pp. 25-46). Routledge.

Kerstetter, D., & Bricker, K. (2009). Exploring Fijian’s sense of place after exposure to tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (6), 691-708.

Kneafsey, M. (1998). Tourism and Place Identity: A case-study in rural Ireland. Irish geography, 31 (2), 111-123.

Lew, A. A. (1989). Authenticity and sense of place in the tourism development experience of older retail districts. Journal of Travel Research, 27 (4), 15-22.

Liu, Z. (2003). Sustainable tourism development: A critique. Journal of sustainable tourism, 11 (6), 459-475.

Liu, S., & Cheung, L. T. (2016). Sense of place and tourism business development. Tourism Geographies, 18 (2), 174-193.

Mang, P., & Reed, B. (2012). Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Building Research & Information, 40 (1), 23-38.

McIntyre, N., Williams, D. R., & McHugh, K. E. (Eds.). (2006). Multiple dwelling and tourism: Negotiating place, home and identity. C

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1957). Fenomenología de la percepción. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Mendoza, C. A. L. (1970). Los comentarios de Santo Tomás y de Roberto Grosseteste a la Física de Aristóteles.

Ogunseitan, O. A. (2005). Topophilia and the quality of life. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113 (2), 143-148.

Oakes, T. S. (1993). The cultural space of modernity: ethnic tourism and place identity in China. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 11 (1), 47-66.

Pérez, A. O. (2018). La influencia de Jakob von Uexküll en la filosofía alemana del siglo XX. Ensayos de Filosofia, 8 (2).

Shaw, G., & Williams, A. M. (2004). Tourism and tourism spaces.

Tan, S. K., Tan, S. H., Kok, Y. S., & Choon, S. W. (2018). Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage–The case of George Town and Melaka. Tourism Management, 67, 376-387.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1974). Topophilia: A study of environmental perceptions, attitudes, and values. Prentice-Hall.

Ryan, C. (Ed.). (2007). Battlefield tourism: History, place and interpretation. Routledge.

Smith, S. (2015). A sense of place: Place, culture and tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 40 (2), 220-233.

Stokowski, P. A. (2002). Languages of place and discourses of power: Constructing new senses of place. Journal of leisure research, 34 (4), 368-382.

Walsh, J. A., Jamrozy, U., & Burr, S. W. (2001). Sense of place as a component of sustainable tourism marketing. Tourism, recreation and sustainability, 195-216.

Approach to the Tourist Space from the Sense of Place